STUDENTS GRAPPLE FOR GRADING FAIRNESS AMIDST

COVID-19:

An archive of the discussion and resolutions passed at the 7C’s in relation to campus lockdown.

ANALYSIS:

Coronavirus has disrupted education on a global scale. Colleges have been forced to close and move their courses online, leaving students with questions about their education and what COVID-19 means for their future. For a lot of low-income or international students, college is their sanctuary: the one place where they have constant access to food, shelter, stable internet access, and work-study jobs. The pandemic has exacerbated the shortcomings that a lot of students from underrepresented backgrounds face on a day-to-day basis. For several students, their learning environment at home is now subject to circumstances outside of their control. Some of these factors include but are not limited to: domestic abuse, gun violence, financial instability, housing insecurity, time zone disparities, and lack of access to mental health resources. With the majority of students off campus, colleges are limited in their ability to help remedy the issues mentioned which are likely to directly impact a student’s academic performance.

To alleviate stress and pressure during these unprecedented times, colleges across the nation have begun implementing a universal pass-fail grading system for the spring semester. Some students believe that normal grading policies during these times are unproportionately unfair to those struggling with access to quiet study spaces, a stable home, health, and family responsibilities. Others believe students should be given the option to keep their grades, especially when they need a GPA boost to get into the graduate and medical school of their dreams, or simply need a fixed GPA to keep their scholarships. This complex debate over what the most optimal option is, has divided higher-education administration, faculty, and students alike.

As of April 17th, Pomona College has become the only member of the Claremont Colleges to officially adopt a universal pass/incomplete/”no record pandemic” grading policy for Spring 2020. All students with a letter grade of A through D will automatically receive a "Pass", with no option to opt-in to a letter grade. Those not in the position to pass a class, can request an “incomplete” given the option of finishing the coursework next semester to earn a passing grade. If a student is not in the position to pass a class and they do not want to take an incomplete, an “NRP” would show on their transcript. No credit is awarded for the course if a student opts for a “no record pandemic”. “No record pandemic” indicates the final grade notation was caused by an unprecedented pandemic.

This came in response to weeks of intense debate and discourse between students and faculty. For proponents of a universal pass/incomplete system, pass/incomplete was the only equitable option. They argued that students who were least affected by the pandemic would be the only ones opting into letter grades, disregarding the remaining students who found themselves in disadvantaged circumstances. A large number of Pomona students even considered an academic strike if Pomona did not adopt the universal pass/incomplete policy. Methods of striking included refusing to attend online class and not submitting assignments, attending Zoom classes with "#pomstrike2020" graphic displayed, and boycotting course registration for the Fall 2020 semester. However, they did not have to reach those limits in order to obtain their desired outcome, as the administration agreed to the P/I policy. Nevertheless, not everyone is satisfied with Pomona’s universal policy, and parents have now joined the debate about what “fair” looks like.

Pomona is now being sued by a few current students and their parents over the college’s decision to move into a universal P/NC policy. They claim that a denial of a grade is some sort of “breach of contract”. Some Pomona parents and alumni alike, are dismayed that the faculty made the decision without consulting with parents. There are parents across the board who are concerned that students who want to keep their grades are being penalized. They prefer a system that allows grades for those who want them, while still giving a choice to opt out for those who don’t. How can one determine what the majority of students want? And can a majority overshadow a silent minority?

In an attempt to urge the Claremont Colleges to adopt policies that address the myriad and diverse concerns of all the students, a group of students known as the 5C Students for Grade Equity, surveyed nearly 2,600 students at the Claremont Colleges. They assessed students’ change in learning environment, and collected their opinions on various grading policies. The survey asked a broad set of questions relating to students’ socio-economic class, status as a domestic vs. international student, and other identifying factors. Out of those surveyed, 554 were low-income students and 2,031 were non-low-income. When asking about student access to suitable academic space, the survey found across the board that being at home was worse for learning space than being at college --- this differential was larger for self-identified low-income students compared to non-low-income students. Out of those who were low-income, only 46% had strong reliable wifi, 26% had a quiet workspace, and 57% had a desk. For the surveyed non-low-income students, 63% had strong wifi, 50% had a quiet workspace, and 80% had a desk of their own. With such a different learning environment that the one that students were accustomed to on campus, what grading policy would students think best accommodates them?

Across the broad student body, students were highly in favor of grade inflation and a grade floor (making a B+ the lowest possible grade). Eighty percent of those surveyed favored a B+ grade floor, while universal pass only had a little less than 50% of the votes.

Students who were low-income, first-generation, and on financial aid, too favored a grade floor. Eighty-seven percent of all first-generation students preferred grade inflation over universal pass-fail. Seventy percent of students across the student body stated they were depending on Spring 2020 grades for a GPA boost. This data was compiled into an extensive 30-page report, and sent to the administration across the Claremont Colleges --- it formed the solid foundation for the policies that different schools would end up implementing.

Claremont Mckenna’s student body presented a short, yet concise analysis of the 30-page report to administration during a faculty meeting. Student representatives of ASCMC had 10 minutes to speak on the proposed grading policies and answer any follow-up questions. A few minutes into the meeting, a faculty member shared that he did not understand why students were a part of a meeting that was only “intended” for faculty. He did not like the idea of having students at the meeting and issued a motion to move the meeting into Executive Session, effectively removing non-voting members and removing students. The students were moved to Zoom’s waiting room and told to wait in case anyone wanted to bring them back at any point throughout the meeting. The meeting lasted nearly four hours and they were never brought back in. They had been voted to be removed and were barred from the voting deliberations, but that did not make the meeting any shorter. A one hour meeting quickly turned into a 4-hour one. It was clear faculty did not see eye to eye on this issue. Students were later notified that standard grades would be kept, and the deadline to opt into a CR/NC course was extended until students are able to view their grades in May.

Another collective of students at Scripps, Pitzer, and Claremont Mckenna College organized to urge their administrations to formally adopt universal pass. On social media, they are known as @NobodyFailsatScripps, @NobodyFailsatPitzer, and @NobodyFailsatCMC. They have branded themselves as the coalition of students who are mobilizing to fight for equity. Some of the leaders of these groups had also participated in the aforementioned study and favored a grading adjustment and grading floor combination, but argued that their responses were made before they got a real taste of online classes, and were not as informed as they are now. NobodyFailsatCMC organizer Katherine Almendarez, argues that for many students, “grades are [now] secondary to family responsibilities, health conditions, immigration issues, unstable housing and time zone differences”. For her, the movement is an opportunity for CMC to do what is “morally right”. She goes on to say that “instead of our representatives, professors and administrators trying to alleviate our hardships”, she believes students are “being penalized for being poor and marginalized”. In an article describing what true inclusivity looks like, Laleh Ahmad CMC ‘20, another supporter of NobodyFails at CMC, said “a universal pass policy wouldn’t have been ideal for a lot of people, including myself, but we often have to sacrifice what we want in order to be truly inclusive.” It is unlikely for one academic policy to favor every individual person, especially when it has such a strong impact on one’s education. But are people willing to make sacrifices for the greater good? And what truly constitutes the “greater good”? When it comes down to become inclusive at liberal institutions that celebrate diversity and inclusivity, will people step up?

It is a misconception to believe that all students who come from disadvantaged communities support universal pass ― further complicating the debate on which policy is “right”. Take this testimonial from a CMC student who strongly affirms that a universal policy hurts more than it helps.

“I think that the policy that CMC has provided us is more than fair to all students. I am disappointed by the notion that if we do not agree with the Universal Pass, we do not care about our fellow classmates. I am a low income student on full financial aid, I share a bedroom with my two brothers, and I do not have a quiet or personal workspace, but I strongly believe that it is not appropriate that all CMC students should be compelled to forfeit their opportunity (and right) to earn letter grades because of my particular circumstances. Neither is it fair to me that I should be prevented from attaining the grades I have been working so hard to earn. I believe that the “equitable” choice of universal pass hurts more people than it helps. We cannot base our decisions on the assumption that even if it helps only one person it is worth it — because that is simply not how life works. The answer should be to advise faculty to be extremely sensitive and lenient with students who express necessity for extra consideration. Those few students may therefore be afforded extra consideration, and those of us committed and can work hard despite obstacles and who take pride in earning our grades can thus be allowed to reap the rewards of our efforts, without taking away from those requiring extra help.”

COVID-19 has put people around the globe in uncomfortable situations. People have broken friendships over this issue of grading adjustments. We have students who favor the traditional form of grading, those who prefer grading with some form of grade inflation, and those who advocate for either a universal A, or a universal pass. The more research I do, the more I am inclined to believe that consensus on this issue will never be made. Not all students are on board with the idea of “upgrading”. Every student is calling for compassion but compassion looks differently for everyone. Some want to keep grades to represent their hard work throughout the semester. Others simply don’t have the means to maintain good grades despite also working hard. Then there are those who need grades to graduate. There are some rising seniors ― some of which are low-income ― who are double majoring and need to overload the next school year in order to graduate on time. In order to overload, students at the Claremont Colleges typically require a 10.5 GPA, on a 12 point scale. Without their grades this semester, they can not do that. Unless a universal pass policy lets students overload without the GPA requirement, there would be a few students who could potentially not graduate with a universal pass. None of the advocates of universal pass included a provision to disregard the GPA minimum this semester, for students who are seeking to overload in courses for the fall semester.

On April 23, a concerned international alumna from Scripps anonymously submitted an opinion piece to the Claremont Independent newsletter, expressing her belief that a universal pass would negatively impact the Scripps community as a whole. In her piece, she mentioned having struggled with her GPA because of her depression and anxiety caused by family issues, but recognized that her professors’ support and encouragement helped her pass her courses. She then compared adopting universal pass, to party members in China being forced to donate money to fight COVID-19 while the media proudly claimed to have raised millions to help Wuhan. She goes on to say that “good will and coerced charity are two different things, where oftentimes the latter sours the former, we tend to smile ruefully”. In her eyes, colleges must do things to address the difficulties that different community members are facing, but not through a “reductive and questionable equalizing tactic that forces people to be chevaliers.” She believes that coercion, and in this case, universal pass, is not the answer.

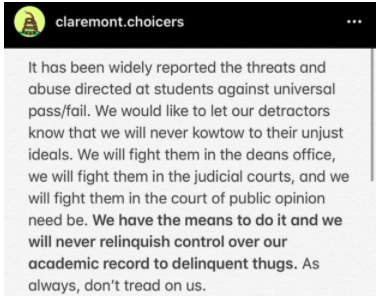

And just when we thought people couldn’t be more divided on this issue, more clamour arose. On the other side of the debate, a few students who were deeply committed to fighting for maintaining the traditional grading system, attempted to start a social media movement ― one that was cut short due to their hateful slander of students in unprecedented circumstances. @claremont.choicers on Instagram branded themselves as the “Claremont students for preserving and reinstating traditional letter grades at the 5C’s”. For their first post, Claremont Choicers made a ringing statement announcing they “strongly detest any universal pass/fail grading as a form of theft of labor” and went on to claim that they “would be damned to excuse [their] phantom privilege for an imbecile’s haughty incompetence”. Who are the incompetence imbeciles? Students from disadvantaged backgrounds who were not in stable households during the pandemic, or simply those who could never hold a GPA as high as theirs? Afterall, they did call the people leading the NobodyFails movement delinquent thugs.

@Claremont.choicers made three public posts. This image was the second one.

As is evident, Claremont Choicers were willing to fight to the bone and would do so in court if needed. After all, it is safe to assume that they either come from a wealthy family, or simply have the “connections” in court to rule in their favor. With just three posts, Claremont Choicers proved that socioeconomic status may play a dominating factor in the perception that one has on these policies. Shortly after the creator of the site was exposed, the page was taken down. So much for trying to be anonymous right? Students thought they’d be able to hide behind a screen, but when you use demeaning language with the intent to hostilize students with a differing opinion from yours, your identity gets discovered within minutes.

As student movements continued, the conversation on equity intensified and new decisions were made. On April 29, Pitzer College became the only 5C to grant a universal A system, just under another name. All students with the minimum passing grade of a D-, would be given a “Satisfactory Pandemic/No Record Pandemic” notation on their transcript, but each SP would be recorded in the GPA as equivalent to an A. In this rare case, enacting a universal pass came with a GPA boost. The movement was spearheaded by a group of 6 first-generation, low-income students at Pitzer and various students across the Claremont Colleges congratulated them for making history. The outcome truly was phenomenal and historical. No one really expected any form of universal A system to be adopted. However, questions have now risen over whether universal As will devalue the tuition paid to these universities and whether jobs will even bother taking transcripts from Pitzer College seriously. There are also some professors, primarily those who are visiting and not tenured, who are concerned with getting in trouble with “the big boss” if too many A’s are given. Is it possible that that will affect their ability to keep their profession in the future?

I have concluded that people will never see eye-to-eye on this conversation about what fair and equitable grading looks like. Everyone has their own biases and will continue to do so. People tend to be in support of decisions that benefit themselves because that is how human nature works. However, it is important to remember that we are living in a pandemic ― one that no one anticipated to be in. It is affecting everyone. Professors and students alike did not sign up to move onto online classes at the beginning of the year. We are all learning how to adjust to them ― some better than others. We might not get the policy that we want, but some sacrifices do need to be made in order to be inclusive. Now it all comes down to determining who gets to make that call and who specifically needs to make those sacrifices. You decide.

The intention of this piece was to inform audiences about the different policies the Claremont Colleges have adopted, and the student movements that influenced those decisions. It hopes to encourage readers to make their own judgements about what policy they believe to be equitable. This research presented contrasting viewpoints on grading, which still today, has not reached a unified consensus.

Diana Hernandez is a rising senior at Claremont Mckenna College, double majoring in Government and Media Studies. Her research focuses on how media as a platform, has the power to influence a community’s cultural beliefs, spark social movements, and determine which topics dominate conversations. She enjoys making edgy visuals, zines, and triptych poster series to make statements about issues affecting her community.